Shoebill

- December 11, 2023

- 0 comment

The shoebill (Balaeniceps rex) is a large stork-like bird found in the swamps of eastern and central Africa. It is the only living member of the family Balaenicipitidae, and is one of the most iconic and recognizable birds in Africa.

Physical Appearance

Shoebill

- Lifespan: 30-35 years

- Habitat: Freshwater Swamps and Marshes, Seasonally Flooded Grasslands and other Wetland habitats.

- Diet: Fish, Frogs, Snakes, and Small Mammals.

- Size: 5 Feet

- Weight: 15 lbs

- Wingspan: 8 feet

- Conservation Status: Risk of Extinction.

- Population Trend: The population of shoebills is declining. It is estimated that there are only about 5,000-8,000 shoebills left in the wild.

The most striking feature of the Shoebill is its large shoe-shaped bill, which gives the bird its name. The bill is massive, bulbous, and somewhat shoe-like, featuring sharp edges that assist in capturing and handling prey. The bird’s overall appearance is complemented by a tall crest on its head and a bluish-gray plumage.

Feather Coloration

The shoebill’s plumage is primarily a pale slate gray with a hint of blue, particularly on the wings. This coloration serves as camouflage in the shoebill’s swampy habitat, blending in with the reeds and papyrus plants. The underparts of the shoebill are slightly lighter, with a whitish hue.

- A small feathered crest on the back of the head, which is usually more pronounced in males.

- A bright yellow iris, which contrasts sharply with the gray plumage.

- A red throat pouch, which becomes more prominent during courtship displays.

The shoebill’s plumage is relatively uniform in color throughout the year, with no significant seasonal variations. Young shoebills have a slightly paler plumage than adults, and their bills are a more brownish color.

Flight Characteristics

Despite their large size, shoebills are relatively poor fliers. Their wings are broad and rounded, but they are not well-proportioned for sustained flight. Shoebills typically fly short distances, usually only a few meters at a time. They take off with a running start and flap their wings slowly and deliberately. In the air, they tend to glide more than they flap, and they often land with a splash in the water.

Takeoff speed: Shoebills need a running start to take off, and they can only reach a takeoff speed of about 15 kilometers per hour (9 miles per hour).

Flight speed: Shoebills typically fly at a speed of about 20-30 kilometers per hour (12-19 miles per hour).

Maximum flight distance: Shoebills are not known to fly long distances. The longest recorded flight of a shoebill was about 1 kilometer (0.6 miles).

Flight maneuverability: Shoebills are not very maneuverable in flight. They have difficulty making tight turns and can only change direction slowly.

Landing: Shoebills often land with a splash in the water. They can also land on land, but they need a large area to do so.

Migration Patterns

Shoebills are considered to be non-migratory birds, meaning they do not undertake long-distance seasonal movements. They typically reside within their established territories throughout the year, utilizing the available resources within their wetland habitats. However, shoebills may exhibit some localized movements within their home ranges in response to changes in food availability or water levels.

While shoebills are generally considered to be non-migratory, there have been some instances of individuals dispersing beyond their usual ranges. These movements are thought to be driven by factors such as habitat loss, competition for resources, or the search for new mates.

Habitat & Distribution

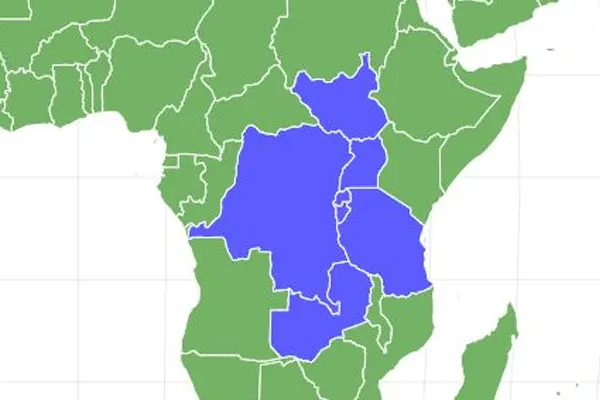

The shoebill’s distribution range extends from southern Sudan to Zambia, encompassing countries like Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Within these regions, they inhabit specific wetland areas such as the Sudd swamp in South Sudan, the Malagarasi wetlands in Tanzania, and the Bangweulu swamp in Zambia.

South Sudan: Shoebills are found primarily in the Sudd swamp, a vast wetland system along the White Nile River.

Uganda: Shoebills inhabit the papyrus swamps along the Victoria Nile River and Lake Victoria.

Rwanda: Shoebills are found in the Akagera National Park, which includes papyrus swamps and grasslands.

Tanzania: Shoebills reside in the Malagarasi wetlands, a protected area known for its rich biodiversity.

Zambia: Shoebills are found in the Bangweulu swamp, a vast wetland system in the northeastern part of the country.

These wetland habitats provide essential resources for shoebills, including food, shelter, and nesting sites. The dense vegetation and shallow waters offer ideal conditions for shoebills to hunt for fish, frogs, and other aquatic prey.

Behavioral Traits

Shoebills exhibit a range of fascinating behavioral traits that reflect their unique adaptations to their environment and their solitary lifestyle. Their hunting techniques, vocalizations, courtship rituals, and parental care demonstrate the complexity of their behavior and the importance of conserving these remarkable birds.

Shoebills exhibit a range of fascinating behavioral traits that reflect their unique adaptations to their environment and their solitary lifestyle. Their hunting techniques, vocalizations, courtship rituals, and parental care demonstrate the complexity of their behavior and the importance of conserving these remarkable birds.

Role in Ecosystem

Shoebills play a significant role in maintaining the ecological balance and biodiversity of wetland ecosystems. Their presence as apex predators, their contribution to nutrient cycling, and their potential as bioindicator species underscore their importance in the ecosystems they inhabit.

Predator-Prey Dynamics: As apex predators, shoebills regulate populations of their prey, primarily fish and amphibians. Their hunting activities help maintain a balance in the food chain, preventing overpopulation of prey species and ensuring the survival of other organisms that rely on these prey as food sources.

Nutrient Cycling: Shoebills contribute to nutrient cycling by consuming and excreting nutrients. Their waste products release valuable nutrients back into the ecosystem, supporting plant growth and the overall productivity of the wetland environment.

Seed Dispersal: Shoebills may inadvertently aid in seed dispersal by consuming fruits and excreting the seeds along with their droppings. This can help disperse plant species and promote the regeneration of vegetation in their habitat.

Dietary Habits

Their diet varies depending on the availability of prey in their habitat. In areas with abundant lungfish populations, shoebills heavily rely on this fish as their primary food source. However, they will readily consume other prey items, such as frogs, snakes, monitor lizards, and even young crocodiles.

Their ability to stand still for extended periods and their keen eyesight make them effective ambush predators. Shoebills typically consume their prey whole, swallowing it headfirst. They have strong stomach acids that help digest their prey, including bones and scales.

Shoebills typically forage for food during the day, but they may also hunt at night, particularly in areas with nocturnal prey species. Their diet varies seasonally, reflecting changes in prey availability. During the dry season, when fish populations decline, shoebills may rely more heavily on amphibians, reptiles, and small mammals.

Interesting Facts

The shoebill is a unique bird with no close relatives. It is the only living member of the family Balaenicipitidae, which is thought to have diverged from other stork-like birds over 50 million years ago.

- They have a distinctive shoe-shaped bill: The most distinctive feature of the shoebill is its enormous, shoe-shaped bill. The bill is about 20 cm (8 inches) long and 15 cm (6 inches) wide and is used for catching fish and other aquatic prey.

- They are found in swamps and marshes in eastern and central Africa: Shoebills are found in freshwater swamps and marshes in eastern and central Africa. They prefer to live in areas with tall papyrus reeds, which they use for shelter and breeding sites.

- They are solitary birds and do not form large flocks: Shoebills are solitary birds and do not form large flocks. They typically maintain their own territories and only interact with other shoebills during breeding season.

Nesting Habits

Shoebills are monogamous birds, and they form strong pair bonds that can last for several breeding seasons. Breeding typically occurs during the rainy season, when food is most abundant. Both parents are involved in nest building. The nest is a large, flattish platform that is often partially submerged in water. The platform is made of reeds, grasses, and other vegetation. The nest can be up to 3 meters (9.8 feet) wide and 1 meter (3.3 feet) deep.

- Incubation: The female lays one or two eggs, which are incubated by both parents for about 30 days. The eggs are white and about the size of footballs.

- Chick rearing: When the chicks hatch, they are blind and helpless. Both parents feed the chicks regurgitated food, which consists of fish, amphibians, and other small animals. The chicks fledge at about 105 days old.

- Nesting sites: Shoebills typically nest on floating platforms or on small islands. They prefer to nest in areas with tall papyrus reeds, which provide shelter and protection from predators.

- Threats to nests: Shoebill nests are vulnerable to predation by monitor lizards, snakes, and other animals. They are also threatened by human disturbance, such as fishing and boat traffic.

Calls & Vocalizations

Shoebills are relatively silent birds, but they do produce a variety of vocalizations, including grunts, growls, hisses, and bill-clattering. These vocalizations are used for a variety of purposes, including territorial defense, courtship displays, and attracting mates.

- Grunts: Shoebills grunt to communicate with each other, particularly when they are foraging or feeling threatened.

- Growls: Shoebills growl to warn intruders away from their territories.

- Hisses: Shoebills hiss to defend their nests and chicks from predators.

- Bill-clattering: Shoebills clatter their bills during courtship displays and aggressive encounters. This is a loud, staccato sound that is produced by rapidly snapping the upper and lower mandibles together.

Shoebill vocalizations are an important part of their communication system and help them to survive and reproduce in their wetland habitats.

Ecological Significance

Shoebills play an important ecological role in the African wetlands they inhabit. They are apex predators, meaning they sit at the top of the food chain and help to regulate populations of their prey, such as fish and amphibians. This helps to maintain the balance of aquatic food webs and ensures that prey populations do not grow too large, which could damage the ecosystem. They consume nutrients from their prey and then excrete them back into the environment, where they can be used by plants. This helps to support plant growth and the overall productivity of the wetland ecosystem.

The presence of shoebills is also considered an indicator of a healthy wetland ecosystem. They are sensitive to habitat degradation and pollution, so their decline can be a sign that an ecosystem is in trouble. As a result, shoebills are valuable bioindicator species that can be used to monitor the environmental health of wetland ecosystems.

Finally, shoebills are an important ecotourism attraction. They are charismatic and iconic birds that draw tourists to wetland areas. This can generate revenue that can support local communities and conservation efforts. Shoebills can also raise awareness about the importance of wetland conservation and encourage people to take action to protect these vital ecosystems.

Conservation Status

The shoebill (Balaeniceps rex) is currently classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. This means that it is at risk of extinction in the wild.

- Habitat loss: The shoebill’s habitat is being lost due to human encroachment, such as agriculture, deforestation, and draining of wetlands.

- Hunting: Shoebills are hunted for their meat and feathers.

- Pollution: Pollution of the shoebill’s habitat is a major threat, as it can contaminate their food and water sources.

- Establishing protected areas: Protected areas are being established to provide shoebills with safe havens from human encroachment and poaching.

- Educating local communities: Local communities are being educated about the importance of shoebills and the threats they face.

- Working to reduce hunting and pollution: Efforts are being made to reduce hunting and pollution of the shoebill’s habitat.

- Captive breeding programs: Captive breeding programs are being used to help increase the shoebill population.

If these conservation efforts are successful, the shoebill may have a chance of surviving in the wild. However, the shoebill still faces a number of challenges, and it is important to continue to work to protect these unique and endangered birds.

Research and Ongoing Studies

Shoebills are fascinating and enigmatic birds that have intrigued scientists for centuries. Despite their iconic status, there is still much to learn about their biology, ecology, and conservation needs. Ongoing research efforts are focused on addressing these knowledge gaps and informing conservation strategies to protect these vulnerable birds.

- Shoebill Monitoring and Conservation in Uganda: This long-term project monitors shoebill populations in Ugandan wetlands, providing valuable data on population trends, habitat use, and breeding success.

- Shoebill Diet and Foraging Ecology in Zambia: Researchers are investigating the diet and foraging behavior of shoebills in Bangweulu Swamp, Zambia, using a combination of field observations, stomach content analysis, and stable isotope analysis.

- Shoebill Habitat Use and Selection in South Sudan: This study is assessing the habitat preferences of shoebills in the Sudd swamp of South Sudan, identifying critical habitat components and evaluating the impact of human activities.

- Shoebill Captive Breeding Program at Uganda Wildlife Conservation Education Centre: This program aims to establish a self-sustaining captive population of shoebills, develop effective breeding and rearing techniques, and explore potential reintroduction strategies.

- Shoebill Conservation Education and Outreach in Rwanda: This project is raising awareness about shoebills and their conservation needs among local communities in Rwanda, promoting sustainable practices, and fostering community involvement in conservation efforts.

These ongoing research efforts are contributing significantly to our understanding of shoebills and their conservation needs. The knowledge gained from these studies is informing conservation strategies, influencing policy decisions, and enhancing our ability to protect these remarkable birds.

Educational and Ecotourism Opportunities

Shoebills, with their unique appearance, intriguing behavior, and ecological significance, present a wealth of educational and ecotourism opportunities. These charismatic birds can serve as ambassadors for wetland conservation, raising awareness about the importance of these threatened ecosystems and inspiring action to protect them.

- Schools and Educational Institutions: Shoebills can be incorporated into school curricula, introducing students to the wonders of biodiversity, adaptations, and ecological roles of birds. Their fascinating hunting techniques, unique bill shape, and solitary nature can spark curiosity and inspire a lifelong interest in ornithology and conservation.

- Public Lectures and Workshops: Engaging presentations and workshops can inform the public about shoebills, their conservation status, and the threats they face. These events can highlight the importance of wetland ecosystems and the role of shoebills as bioindicators of ecosystem health.

- Interactive Exhibits and Educational Materials: Museums, nature centers, and zoos can develop interactive exhibits and educational materials featuring shoebills. These exhibits can showcase their biology, behavior, and conservation challenges, using engaging multimedia displays, hands-on activities, and captivating stories.

- Citizen Science Programs: Citizen science initiatives can involve the public in shoebill monitoring, data collection, and research projects. These programs can foster a sense of connection to nature, promote environmental stewardship, and provide valuable data for shoebill conservation.

- Online Resources and Educational Media: Engaging online resources, such as virtual tours, interactive websites, and educational videos, can provide a broader audience with access to information about shoebills and their conservation needs.

By harnessing the educational and ecotourism potential of shoebills, we can raise awareness about wetland conservation, promote sustainable practices, and generate revenue for local communities, creating a synergy between conservation and economic development. Shoebills can serve as ambassadors for these vital ecosystems, inspiring action to protect their unique habitats and the rich biodiversity they support.

Conclusion

The shoebill, a captivating creature with an ancient lineage, stands as a testament to the remarkable diversity and resilience of life on Earth. Its distinctive shoe-shaped bill, solitary nature, and enigmatic behavior have captivated the imaginations of scientists and birdwatchers alike. As an apex predator, shoebills play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of aquatic ecosystems, regulating prey populations, and contributing to nutrient cycling.

Despite their ecological significance, shoebills face an uncertain future. Habitat loss, hunting, and pollution threaten their survival, pushing them to the brink of extinction. Conservation efforts are underway to protect these remarkable birds, establishing protected areas, educating local communities, and reducing threats to their habitat.

The future of shoebills hinges on our collective efforts to safeguard their wetland havens and ensure their continued presence in the intricate tapestry of life. By preserving these enigmatic birds, we not only protect a unique species but also safeguard the fragile ecosystems upon which they depend. Let us rise to the challenge of protecting shoebills, ensuring their continued existence as symbols of resilience and hope amidst a changing world.

Leave your comment