Black-footed Ferret

- April 1, 2024

- 0 comment

The Black-footed Ferret, a charismatic and elusive member of the Mustelidae family, is an emblem of both resilience and conservation efforts. Once believed extinct in the wild, these small, nocturnal predators have been the focus of intensive recovery programs since their rediscovery in 1981. With distinctive black markings on their feet, masked faces, and long, slender bodies, Black-footed Ferrets inhabit vast prairie ecosystems across North America. They are highly specialized hunters, preying primarily on prairie dogs, relying on these burrowing rodents for both food and shelter. However, their survival became imperiled due to habitat loss, poisoning campaigns aimed at controlling prairie dog populations, and disease outbreaks like sylvatic plague.

Through collaborative conservation initiatives involving federal agencies, zoos, and conservation organizations, significant strides have been made in restoring Black-footed Ferret populations. Captive breeding programs have played a pivotal role, providing a safety net for the species while habitat restoration efforts continue. Reintroduction projects, carefully managed to ensure genetic diversity and minimize disease transmission, have successfully established ferret populations in select locations. Despite progress, challenges persist, including ongoing threats from habitat fragmentation, disease, and climate change. Nevertheless, the Black-footed Ferret’s remarkable journey from the brink of extinction serves as a beacon of hope, illustrating the power of collective action and dedication to safeguarding biodiversity. As stewards of the natural world, it is our responsibility to continue supporting conservation efforts to ensure the Black-footed Ferret and its prairie ecosystem thrive for generations to come.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Mustela nigripes |

| Common Name | Black-footed Ferret |

| Family | Mustelidae |

| Habitat | Prairie grasslands of North America |

| Appearance | Small, slender body; yellowish-buff fur with black mask and legs |

| Size | Length: 18-24 inches (46-61 cm); Weight: 1.5-2.5 lbs (0.7-1.1 kg) |

| Diet | Mainly feeds on prairie dogs; opportunistic carnivore |

| Behavior | Nocturnal; solitary except during mating season |

| Reproduction | Typically produces litters of 3-5 kits |

| Lifespan | Wild: 2-3 years; Captivity: up to 8 years or more |

| Conservation Status | Endangered |

| Threats | Habitat loss, disease (sylvatic plague), predation, poisoning campaigns targeting prairie dogs |

| Conservation Efforts | Captive breeding programs, habitat restoration, reintroduction projects, disease management |

| Notable Features | Strong sense of smell; specialized for hunting in prairie dog burrows; iconic black markings on feet |

Black-footed Ferret

The black-footed ferret, often hailed as North America’s only native ferret species, holds a significant place in the realm of wildlife conservation. With its distinctive masked face and black feet, this elusive carnivore has captured the imagination of scientists and nature enthusiasts alike. In this article, we delve into the intriguing world of the black-footed ferret, exploring its history, biology, conservation status, and the challenges it faces in the modern world.

Physical Characteristics

Size and Appearance

The Black-footed Ferret (Mustela nigripes) is a small yet charismatic mammal with distinct physical characteristics. Typically measuring between 18 to 24 inches (46 to 61 centimeters) in length, including the tail, and weighing approximately 1.5 to 2.5 pounds (0.7 to 1.1 kilograms), these ferrets have a sleek and slender build. Their bodies are elongated, with short legs and a long, bushy tail that aids in balance and agility.

Black-footed Ferrets are known for their striking coloration, characterized by a yellowish-buff fur coat with a distinctive black mask covering their eyes and muzzle. Additionally, they have black markings on their feet, which give them their name. Their fur is dense and soft, providing insulation against the harsh prairie climate.

Unique Features

Specialized Dentition: Black-footed Ferrets have sharp, pointed teeth adapted for capturing and consuming their primary prey, prairie dogs. Their dental structure reflects their carnivorous diet and hunting behavior.

Scent Glands: Like other members of the mustelid family, Black-footed Ferrets possess scent glands used for communication and territory marking. These glands are located near the anus and on the face, and they play a role in social interactions and identifying individuals.

Nocturnal Behavior: Black-footed Ferrets are primarily nocturnal, meaning they are most active during the night. This behavior helps them avoid predators and minimize competition with diurnal species in their prairie habitat.

Bristled Whiskers: The ferret’s whiskers, or vibrissae, are long and sensitive, aiding in navigation and detecting prey in dark burrows. These specialized whiskers play a crucial role in the ferret’s hunting success, allowing it to navigate its environment with precision.

Burrowing Adaptations: Black-footed Ferrets are highly adapted to life in underground burrows, which they use for shelter and raising their young. Their slender bodies and sharp claws enable them to navigate the tight confines of prairie dog tunnels with ease.

Vocalizations: Black-footed Ferrets communicate through a variety of vocalizations, including chirps, hisses, and chatters. These vocal cues are used for social interactions, signaling alarm, and coordinating during hunting expeditions.

Habitat and Distribution

Native Habitat

The Black-footed Ferret (Mustela nigripes) is native to the grasslands and prairie ecosystems of North America. These habitats typically consist of expansive grasslands, interspersed with patches of shrubs, rocky outcrops, and, most importantly, prairie dog colonies. Black-footed Ferrets are highly dependent on prairie dog burrows for shelter, as well as for hunting their primary prey.

Within their native habitat, Black-footed Ferrets exhibit a preference for areas with a high density of prairie dog colonies, as these provide abundant prey and suitable burrow networks. Healthy grasslands with a diverse array of plant species also contribute to the ferret’s habitat, supporting the prey base and offering cover for hunting and denning activities.

Geographic Range

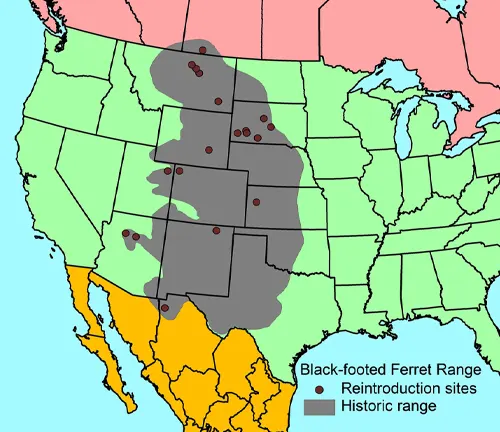

Historically, Black-footed Ferrets ranged widely across the Great Plains of North America, extending from southern Canada through the United States into northern Mexico. However, due to habitat loss, disease outbreaks, and extensive extermination efforts targeting prairie dogs, the ferret’s range has significantly contracted.

Today, Black-footed Ferrets are found in fragmented populations within specific regions of North America where conservation efforts have been successful in reintroducing them. These populations are primarily concentrated in parts of the United States, including Wyoming, South Dakota, Montana, Arizona, and Colorado, as well as in small areas of Canada and Mexico where reintroduction efforts have also taken place.

The geographic range of the Black-footed Ferret is limited by the availability of suitable habitat, particularly areas with healthy prairie dog populations and interconnected grassland ecosystems. Conservation efforts aim to expand the ferret’s range and restore connectivity between fragmented populations to promote genetic diversity and long-term viability of the species.

Behavior and Diet

Social Behavior

Black-footed Ferrets (Mustela nigripes) are solitary animals for much of the year, with individuals primarily interacting during the breeding season. Outside of the mating season, they maintain solitary territories, which they defend from other ferrets, particularly individuals of the same sex.

During the breeding season, which typically occurs in late winter or early spring, male ferrets may engage in aggressive encounters to establish dominance and access breeding opportunities with receptive females. Females give birth to litters of 3 to 5 kits in underground burrows, where they raise their young in seclusion.

While they are primarily solitary, Black-footed Ferrets may exhibit some degree of social behavior, especially during cooperative hunting expeditions or when congregating near prairie dog colonies, their primary food source. They may also communicate through vocalizations and scent marking, particularly to establish territory boundaries and signal reproductive status.

Feeding Habits

Black-footed Ferrets are carnivorous predators with a highly specialized diet centered around prairie dogs (Cynomys species). Prairie dogs make up the vast majority of their diet, and ferrets are highly dependent on them for food. They are well adapted to hunting in the complex burrow systems of prairie dog colonies, where they can locate and capture their prey.

Ferrets typically hunt at night, using their keen sense of smell and hearing to locate prairie dogs within their burrows. They may also employ ambush tactics near burrow entrances or actively pursue prairie dogs above ground. Once they capture their prey, ferrets deliver a swift bite to the neck to incapacitate it before consuming it.

While prairie dogs are their primary prey, Black-footed Ferrets may also opportunistically feed on other small mammals, birds, and insects when prairie dogs are scarce or unavailable. However, prairie dogs remain the cornerstone of their diet, and fluctuations in prairie dog populations can have significant impacts on ferret survival and reproductive success.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Breeding Habits

Black-footed Ferrets (Mustela nigripes) typically breed once a year, with mating occurring in late winter or early spring. Breeding behavior is triggered by environmental cues such as changes in day length and temperature.

During the breeding season, male ferrets may engage in aggressive encounters to establish dominance and gain access to receptive females. Females come into estrus for a brief period, during which they are receptive to mating. Once a female has mated, she will typically give birth to a litter of 3 to 5 kits after a gestation period of approximately 42 days.

Females usually select suitable burrows within prairie dog colonies for birthing and raising their young. They line the nest chambers with grass and fur to create a comfortable environment for the kits. After birth, the mother cares for and nurses her offspring until they are old enough to venture out of the burrow and begin hunting on their own.

Black-footed Ferrets exhibit limited parental care beyond nursing and protecting their young. Once the kits are weaned, typically around 6 to 8 weeks of age, they begin to explore their surroundings and learn essential hunting skills from their mother. Young ferrets may stay with their mother for several months before dispersing to establish their own territories.

Growth Stages

Black-footed Ferrets undergo several distinct growth stages from birth to adulthood:

- Newborn Stage: Kits are born blind, hairless, and completely dependent on their mother for warmth, nourishment, and protection. They spend the first few weeks of life inside the burrow, nursing and growing rapidly.

- Juvenile Stage: As the kits grow, they develop fur, open their eyes, and become more active. They begin to explore the burrow and interact with their littermates and mother. During this stage, they start to transition to solid food and learn basic hunting skills from their mother.

- Subadult Stage: Around 6 to 8 weeks of age, the kits are weaned and become more independent. They start venturing outside the burrow, accompanying their mother on hunting expeditions, and honing their hunting abilities. Subadult ferrets may still rely on their mother for guidance and protection but begin to explore their surroundings more extensively.

- Adult Stage: By around 1 year of age, Black-footed Ferrets reach sexual maturity and become capable hunters and breeders. They establish their own territories and may engage in territorial disputes with other ferrets, particularly during the breeding season. Adult ferrets play a crucial role in maintaining the population and reproductive success of the species.

Threats and Conservation Status

Factors Endangering the Species

The Black-footed Ferret (Mustela nigripes) faces several significant threats to its survival, including:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: The conversion of native grasslands into agricultural land, urban development, and infrastructure projects has resulted in the loss and fragmentation of the ferret’s habitat. Fragmentation isolates populations, reduces genetic diversity, and limits the availability of suitable habitat for foraging and denning.

- Disease Outbreaks: Sylvatic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and transmitted by fleas, poses a severe threat to Black-footed Ferrets. Plague outbreaks can decimate prairie dog populations, reducing the ferret’s primary prey base and increasing competition for limited resources.

- Poisoning Campaigns: Historically, poisoning campaigns targeting prairie dogs as agricultural pests have inadvertently harmed Black-footed Ferrets. The use of rodenticides and other chemical agents to control prairie dog populations can lead to secondary poisoning of ferrets and other non-target species.

- Genetic Bottlenecks: The Black-footed Ferret population experienced a severe genetic bottleneck due to the species’ near-extinction in the 20th century. The loss of genetic diversity increases the susceptibility of individuals to disease, reduces reproductive fitness, and limits adaptive potential in the face of environmental changes.

- Predation: Black-footed Ferrets are vulnerable to predation by larger carnivores such as coyotes, badgers, and raptors. Predation pressure can increase in fragmented habitats where ferrets are more exposed and have fewer opportunities to seek refuge.

Conservation Initiatives

To address these threats and promote the recovery of Black-footed Ferret populations, numerous conservation initiatives have been implemented, including:

- Captive Breeding Programs: Managed breeding programs in zoos and conservation facilities aim to maintain genetic diversity and establish assurance populations of Black-footed Ferrets. These programs provide a safeguard against extinction while habitat restoration efforts continue.

- Habitat Restoration: Conservation organizations and land management agencies work to restore and enhance native grasslands, prairie dog colonies, and interconnected habitats suitable for Black-footed Ferrets. Habitat restoration efforts include removing invasive species, implementing sustainable grazing practices, and preserving critical corridors for species movement.

- Reintroduction Projects: Strategic reintroduction efforts aim to establish self-sustaining populations of Black-footed Ferrets in areas where they have been extirpated or are at risk of local extinction. Reintroduction sites are selected based on habitat suitability, prey availability, and disease risk assessment.

- Disease Management: Conservationists employ various strategies to mitigate the impacts of disease outbreaks on Black-footed Ferrets and their prey. This includes vaccination programs, flea control measures, and monitoring of plague dynamics within prairie dog populations.

- Public Education and Outreach: Public awareness campaigns raise awareness about the importance of Black-footed Ferret conservation and engage local communities in habitat protection and restoration efforts. Education programs highlight the ecological role of ferrets and the importance of preserving native grassland ecosystems.

Challenges Ahead

Ongoing Threats

Despite significant conservation efforts, the Black-footed Ferret (Mustela nigripes) continues to face persistent threats to its survival, including:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Continued habitat loss and fragmentation due to agricultural expansion, urban development, and energy extraction activities threaten the viability of Black-footed Ferret populations. Fragmented habitats isolate populations, reduce genetic connectivity, and limit access to suitable foraging and denning sites.

- Disease Outbreaks: Sylvatic plague remains a significant threat to Black-footed Ferrets, causing periodic outbreaks that can decimate prairie dog populations, the ferret’s primary prey base. Disease management efforts must continue to mitigate the impacts of plague on ferret populations and their habitat.

- Genetic Bottlenecks: The loss of genetic diversity due to historical population declines poses a long-term threat to the adaptive potential and resilience of Black-footed Ferret populations. Genetic bottlenecks increase the susceptibility of individuals to disease, reduce reproductive fitness, and limit the species’ ability to respond to environmental changes.

- Climate Change: Climate change poses emerging challenges to Black-footed Ferret conservation by altering habitat suitability, exacerbating disease dynamics, and increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events. Rising temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, and habitat shifts may further stress ferret populations and their prey.

- Human-Wildlife Conflicts: Encounters with humans, including vehicle collisions, predation by domestic pets, and illegal shooting, pose direct threats to Black-footed Ferrets. Managing human-wildlife conflicts and promoting coexistence with ferret populations are essential for their long-term survival.

Future Conservation Strategies

To address these ongoing threats and ensure the continued recovery of Black-footed Ferret populations, future conservation strategies should focus on:

- Habitat Protection and Restoration: Prioritizing the protection and restoration of native grasslands and prairie dog colonies is essential for maintaining suitable habitat for Black-footed Ferrets. Conservation efforts should emphasize habitat connectivity, landscape-scale conservation planning, and sustainable land management practices.

- Disease Management and Research: Investing in disease monitoring, research, and management strategies is crucial for mitigating the impacts of sylvatic plague and other infectious diseases on ferret populations. Continued research into disease dynamics, vaccination technologies, and flea control measures can inform proactive disease management efforts.

- Genetic Management: Implementing genetic management strategies, such as translocations, genetic rescue, and population augmentation, can help enhance genetic diversity and reduce the risk of inbreeding depression in Black-footed Ferret populations. Genetic monitoring and adaptive management approaches should guide these efforts.

- Climate Resilience Planning: Integrating climate resilience considerations into conservation planning can help identify and prioritize actions to mitigate the impacts of climate change on Black-footed Ferret habitats and populations. This may include habitat modeling, scenario planning, and adaptation strategies tailored to local conditions.

- Community Engagement and Partnerships: Engaging local communities, landowners, and stakeholders in Black-footed Ferret conservation efforts fosters stewardship and support for species recovery initiatives. Collaborative partnerships, outreach programs, and incentive-based approaches can promote coexistence and shared responsibility for conservation.

Different Species

European Polecat

(Mustela putorius)

Found throughout Europe and parts of Asia, the European Polecat resembles the domestic ferret but is larger and more robust.

American Mink

(Neovison vison)

Native to North America, the American Mink is semi-aquatic and known for its luxurious fur. It has a similar body shape to the ferret but with a longer, sleeker profile.

Siberian Weasel

(Mustela sibirica)

Native to Siberia and parts of Asia, the Siberian Weasel is a small, agile predator with a long, slender body and short legs.

Least Weasel

(Mustela nivalis)

Found in various habitats across Europe, Asia, and North America, the Least Weasel is the smallest member of the weasel family, known for its high metabolism and voracious hunting habits.

Stoat

(Mustela erminea)

Also known as the Short-tailed Weasel, the Stoat is found in Eurasia and North America. It has a distinctive white winter coat and is known for its agility and cunning hunting techniques.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What makes Black-footed Ferrets unique among other mustelids?

Black-footed Ferrets are specialized hunters of prairie dogs, relying on them as their primary food source and inhabiting their burrows for shelter. - How do Black-footed Ferrets reproduce?

Black-footed Ferrets typically breed once a year, with mating occurring in late winter or early spring. Females give birth to litters of 3 to 5 kits after a gestation period of about 42 days. - What are the main threats to Black-footed Ferrets in the wild?

Habitat loss, disease (particularly sylvatic plague), poisoning campaigns aimed at controlling prairie dog populations, and predation are the primary threats to Black-footed Ferrets in the wild. - What is sylvatic plague, and how does it affect Black-footed Ferrets?

Sylvatic plague is a bacterial disease spread by fleas that can devastate prairie dog populations, indirectly impacting Black-footed Ferrets, which rely on prairie dogs for food and shelter. - How do researchers monitor and track Black-footed Ferret populations?

Researchers use a variety of methods, including radio telemetry, camera traps, genetic monitoring, and visual surveys, to monitor Black-footed Ferret populations and track their movements and behaviors. - How long do Black-footed Ferrets typically live in the wild?

In the wild, Black-footed Ferrets have an average lifespan of 2 to 3 years, although some individuals may live longer under favorable conditions. - What is the role of prairie dogs in Black-footed Ferret conservation?

Prairie dogs are essential to Black-footed Ferret conservation as they provide both food and shelter for the ferrets. Conservation efforts often focus on protecting and restoring prairie dog habitat to benefit both species. - Are there any success stories in Black-footed Ferret conservation?

Yes, there have been successful reintroduction projects that have established viable Black-footed Ferret populations in certain areas, demonstrating the effectiveness of conservation efforts. - Are there any ongoing research projects aimed at understanding Black-footed Ferret behavior and ecology?

Yes, researchers continue to study various aspects of Black-footed Ferret behavior, ecology, genetics, and health to inform conservation efforts and improve management strategies. - How do Black-footed Ferrets communicate with each other?

Black-footed Ferrets use a variety of vocalizations, including chirps, hisses, and chatters, as well as body language such as scent marking, to communicate with one another. - What is the historical significance of Black-footed Ferrets in North America?

Black-footed Ferrets are considered a keystone species in prairie ecosystems, playing a vital role in controlling prairie dog populations and maintaining ecosystem balance.

Leave your comment